Hymns for Mr. Suzuki

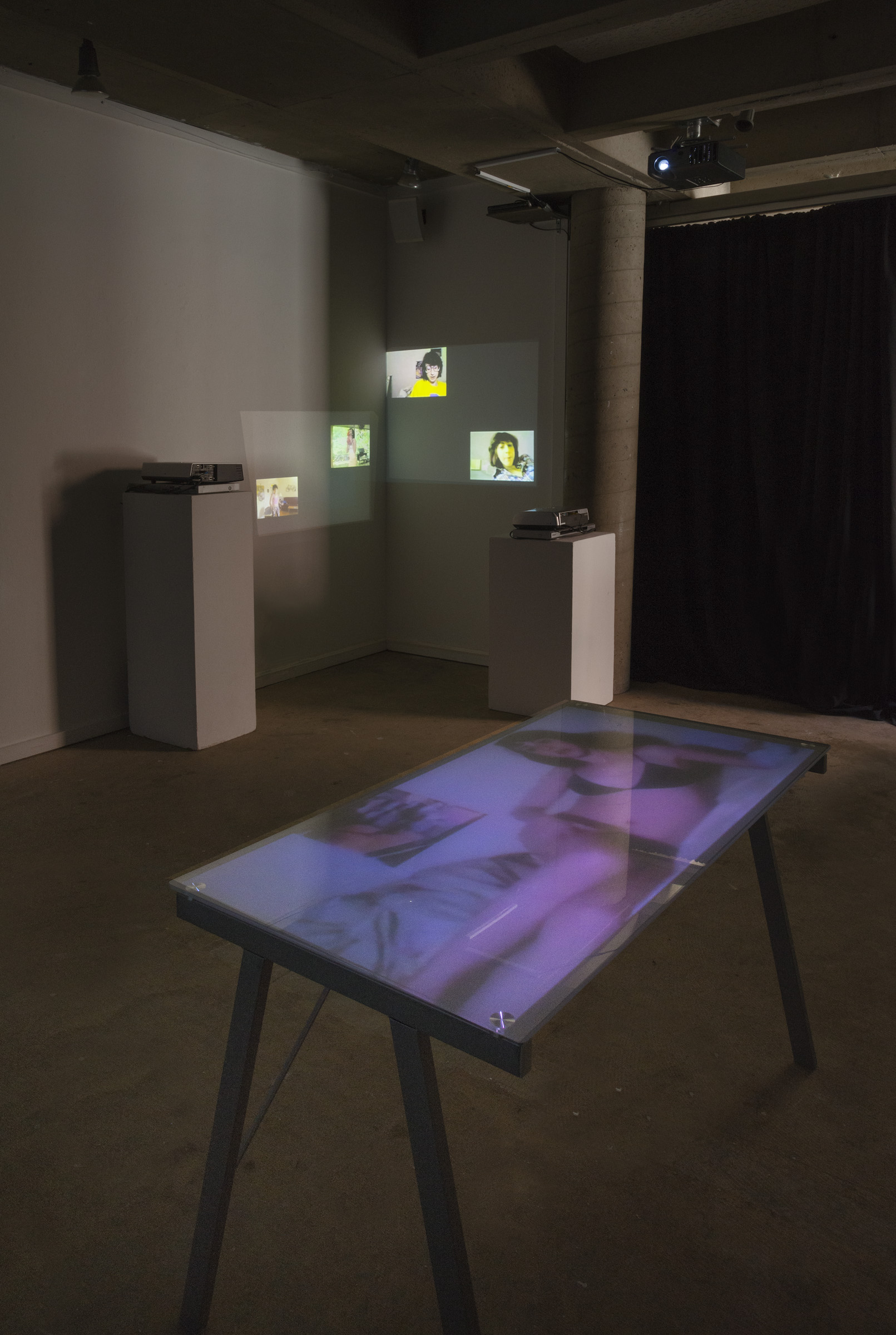

Kate Davis, Cindy Hinant, Ann Hirsch, Servane Mary, Ken Okiishi, Leslie Thornton, Hito Steyerl

Abrons Arts Center

6 September -- 6 October, 2013

Opening Reception: Friday, 6 September, 6-9 PM

The title “Hymns for Mr. Suzuki” denotes an ode to the Japanese pedagogue and violinist Shin'ichi Suzuki (1898–1998), the originator of the Suzuki learning method. A central tenet of this method of music instruction is that all persons can and will learn from their environment, and that we learn most effectively from our native surroundings as children. After the devastation of Japan in World War II, Suzuki sought to lift the spirits of children through teaching them how to see the world through music’s rose-colored lens. When taken in the context of popular culture, the Suzuki learning method points to the ineffable but ardently felt effects of mass media upon the human consciousness. The group exhibition “Hymns for Mr. Suzuki” comprises work that examines how our consciousness has been shaped by popular media and new technology, analyzing how normative ideas about identity, gender and sexuality are conferred through such information streams. This generationally and geographically diverse group exhibition investigates how memory—in this case, memories of mass media—can be understood as a physical inscription onto the brain. Here, the concept of inscription suggests both the collective, unconscious conditioning of people and a potential form of agency: how can we inscribe ourselves into our surroundings? How can we write our own history?

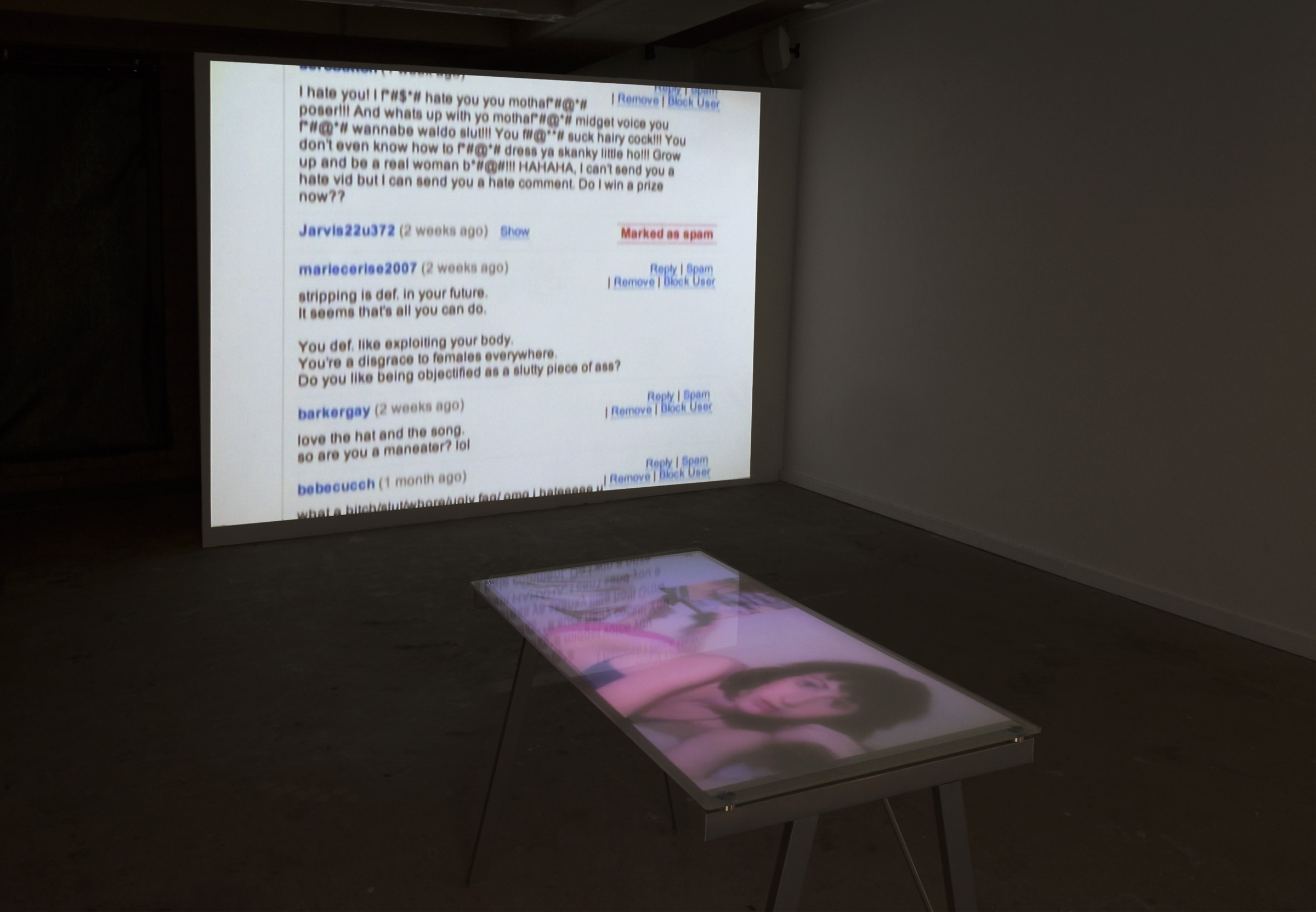

“Hymns for Mr. Suzuki” takes inspiration from video art pioneer Leslie Thornton’s “Peggy and Fred in Hell: The Prologue,” (1985), the first installment of Thornton’s long-running “Peggy and Fred in Hell” video series. Surreal, uncanny, and post-apocaplytic imagery permeates this series tracking Peggy and Fred, two children raised by and unconsciously conditioned through television. In “The Prologue,” we see the children mindlessly reciting songs; Fred singing improvised versions of American ballads while Peggy sings the decidedly age-inappropriate pop hit “Billie Jean” by Michael Jackson. Here, we witness the slips and tangles of identity formation in the making. In addition to Thornton’s “Peggy and Fred in Hell: The Prologue,” “Hymns for Mr. Suzuki” comprises a new installation by Ann Hirsch, titled “The Scandalishious Project: Caca Phony,” presented in tandem with her new eBook “Twelve,” published by Klaus_eBooks, organized by Brian Droitcour; and “Playground,” a forthcoming Rhizome Commission project. Hirsch’s installation looks back at her experience performing as Caroline, a fictional hipster camgirl, as a masters program art project. Here, Hirsch extends conversations on female intellectuality and sexuality, began by artists such as Valie Export and Andrea Fraser, outside the hermeticism of the art world and into the highly visible realm of Youtube. While Thornton’s Peggy and Fred automatically recite pop songs and ballads, Hirsch awkwardly lampoons conventional gestures of sexuality, which are often replicated sincerely in other Youtube users' response videos or publicly ridiculed within the artist's Youtube channel’s comments section.

Glasgow-based artist Kate Davis’s video “Disgrace” finds the artist tracing the contours of her body onto a book of Modigliani drawings, each 10-second shot of the book succeeded by 10-seconds of blackness complemented with a chorus of “boo-hoos.” Simultaneously humorous, bellicose, and self-effacing, Davis’s video combines the often contradictory emotions associated with the feminist impulse to specifically inscribe herself into art history, or to rewrite a patriarchal history—in this case, the canonization of Modigliani, a male artist taking the female form as subject.

Similarly working with the theme of inscription is Cindy Hinant’s “Celebrity Grid (Drastic Measures),” 2013, which superimposes a grid onto a cropped, blown-up image of Amanda Bynes from a celebrity gossip magazine. The grid, here a symbol of rationality, is metaphorically forced upon Bynes, perhaps our most current popular emblem of irrational female recklessness. Further meditating on the stereotype of female irrationality are Hinant’s untitled heart drawings, recalling grade school doodles made by obsessive girls killing class time by channeling her newest beau.

Servane Mary’s works depict iconic, often historical female figures ranging from actors to activists, documenting the evolution of popular female gender identity. In the 2011 wall piece “Untitled (IRA Lavender, Frances Farmer),” we see Amanda Bynes’s progenitor, the similarly troubled actress Frances Farmer. A screen and stage actress known for her involuntary commitment to mental hospitals, Farmer epitomizes the long-standing self-destructive stereotype laid upon women. Mary’s much smaller works comprising mirror plates wrapped with pink stockings invite the viewer to gaze at their own face through the fabric’s mesh, suggesting that the understanding of our own identity is mediated by such constraining forces.

Ken Okiishi’s video “E.lliotT.: Children of the New Age,” (2004), combines references to the popular 80’s movie E.T., a cooking show, and suicide cults in a decidedly elliptical domestic narrative. Here, we see Elliott, played by Sasha Stim-Vogel, and Extra, played by Nick Mauss, wearing matching outfits while talking over each other, “performing” various “new age” activities such as making un-meat loaf. Eventually, Extra dons women’s clothing and puts Elliott (permanently) to sleep. The last scenes, ending with a cacophony of Michael Jackson croons and audio pulled from Spielberg’s E.T., “E.lliotT,” point to a litany of forces upon the identity formation of children in an age of media saturation.

"November" (2004), one of Steyerl’s earlier works, introduces us to her childhood friend Andrea Wolf with footage of the artist’s first film—a sort of Charlie’s Angel’s-meets-kung-fu movie in which these unarmed young women enact violence upon armed, seemingly evil men. Through Steyerl’s narration, we learn that Wolf went on to become a radical leftist activist and member of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, fighting for Kurdish autonomy from German-supported Turkey in the 1990s. After Wolf was executed in Turkey, Steyerl came across a poster emblazoned with Wolf’s face, and positioned in proximity to sex film playbills, in a movie theater, declaring the German activist had been murdered--here we see women becoming metaphorical images by their various objectifications. Steyerl explains how it was by sifting through popular media for images of strong women that she and Wolf replicated gestures of autonomy, sexuality and resistance, and consequently learned how to perform gender. Just as the young women had practiced becoming images of women amidst the innocence of youth, Wolf’s brutal execution in Turkey led to her becoming a martyr, or an image of war.

Thank you to David Everitt Howe, Lia Gangitano, and e-flux.